PJ Ai is a 37-year-old who’s getting used to using a cell phone and navigating Facebook. He’s excited that his friends have offered to teach him the ways of social media. He’s learning to adjust to many things every day — and it’s not just because he’s an intern working as a community health advocate at the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC). Ai has only been out in the free world for a few weeks, after spending more than 20 years incarcerated in state prisons.

APSC runs programs inside prisons and also supports those who have been released to re-enter society and engage in cross-cultural programs that promote racial harmony. Asian Americans make up less than 9 percent of the combined state and federal prison population — a number that is merely an estimate since data is lacking. (Asian Americans have been categorized as “other” throughout much of the prison system.) However, their rates in prison have been increasing, along with a rise in immigration detention and deportation.

Perhaps because the population seems small, Asian Americans often get left out of conversations about criminal justice reform or comprehensive immigration reform, says APSC co-director Eddy Zheng, who served time in prison for a crime he committed as a teenager. “People always look at it as a black and brown issue. They don’t see it as an Asian/Pacific Islander issue,” he says.

But it’s an Asian American issue too, especially for Southeast Asian Americans, who are three to four times more likely to be deported for old convictions than other immigrant communities. PJ Ai’s story is one example, and not an usual one. He is part of a pattern of lawful permanent residents who committed crimes when they were children, served out their sentences, and are still targeted for deportation today.

Ai was born in a Thai refugee camp in 1981, where his parents met after fleeing the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. They resettled in Stockton, CA in 1985. Raised in a neighborhood dominated by gang violence and in a family that shared a history of trauma, Ai was bullied as a child and joined a gang for protection. At 14, he and an adult killed a storeowner during an armed robbery and Ai became one of the youngest children to be tried as an adult in California. He was convicted of second-degree murder and was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

He began his sentence in a youth prison and was transferred to an adult prison after he turned 18. Initially he stayed involved in a gang for protection, putting on a mask of toughness. He wanted to change his path in life, but didn’t know how. “In prison, there’s no model of how to make changes,” he says. “There’s nothing except what’s in front of me, which is really hyper masculine, very violent, aggressive people.”

The turning point came for him in 2004 when he was invited to participate in a Native American program that opened his eyes to the pain he had caused others. He quit the gang and began signing up for all of the educational opportunities he could find. Eventually, he was transferred to San Quentin state prison, which offers more rehabilitative programs. There, he met two members of APSC who were visiting from the outside. Together, they founded an ethnic studies class called ROOTS that addresses the impacts of intergenerational trauma on immigrant and refugee communities.

While in prison, Ai earned an associate’s degree and became a certified counselor in drug and alcohol addiction, rape crisis, and domestic violence. He volunteered with crisis intervention and counseling for other inmates, and worked with at-risk kids who were brought in as visitors to the prison. Recommended for release at his first parole board hearing, he was paroled in 2016, but under harsh new federal immigration policies, was immediately detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Though he had already served out his sentence, his green card had been revoked. He then spent 18 months in ICE detention before being released in May 2018. Today, Ai is still at risk of deportation to Cambodia, a country he’s never visited.

This intersection between the criminal justice and immigration systems is one of the most pressing issues APSC addresses, and one for which it received two grants from the San Francisco Foundation’s Rapid Response Fund. “There are very few organizations that do a mix of the two issues,” says Ben Wang, co-director of APSC.

The San Francisco Foundation grants made it possible for APSC to convene formerly incarcerated Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, their families, and their allies to advocate around issues of incarceration and deportation. The organization is also developing a toolkit of advocacy and organizing models for fighting against deportation, which will be distributed through a series of trainings.

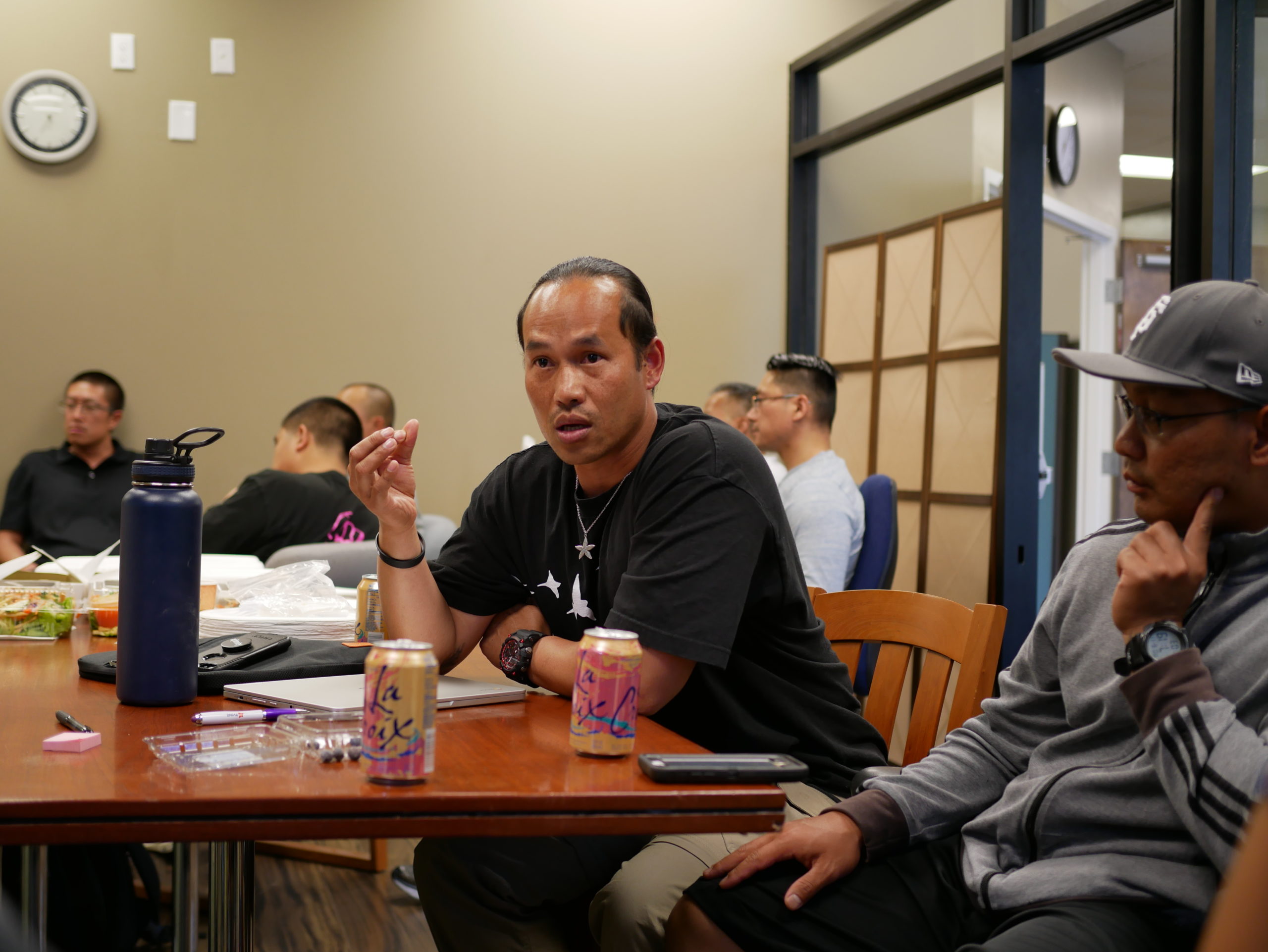

On a recent May evening, 18 people — 8 of them formerly incarcerated — gathered around a table in Oakland Chinatown to discuss anti-deportation efforts. They closed the meeting by asking participants to imagine a world without deportation. What would that look like?

“It means families get to stay together and not get separated,” PJ said, thinking not only of himself, but also the many others families he knows that have been forced apart.

Author: Melissa Hung, foundation consultant