We were new. We had no money at all. … The members of the distribution committee thought that our job was the support of local charities, not things like neighborhood organization, not things like housing, though we did get into both those things later on. But really, the kind of thing that you would classify under social welfare in the old days. That was our business.

John R. May, SFF’s first director

Building the Community Trust

By the early 1950s, the nascent San Francisco Foundation had formed a community trust in the Bay Area and declared that “the future, it is evident, will justify the growing pains, the patience, and the faith which characterized the first three years.” Alongside an inaugural seven-person Distribution Committee chaired by co-founder Daniel E. Koshland Sr., much of those growing pains, patience and faith fell on the shoulders of SFF’s first director, John R. May, who had previously worked at the federal Office of Price Administration to help control consumer prices and stabilize rents once the United States entered World War II.

Laying a Foundation for Racial Equity: The 1950s and 1960s

At the outset, it was May’s “job to publicize the foundation, help make it known among potential donors, lawyers, financial advisors, ‘and to make myself modestly conspicuous among people dedicated to good works.’” It would take time to build our reputation and coffers enough to make real change in the community, and patience was the name of the game.

“John cultivated the community,” recalled May’s successor, Martin Paley, during a 2021 interview. “He built a reputation. People had confidence in him. And so he was able to attract a lot of bequests that didn’t mature until many years after John was gone. And it was to his credit that the foundation grew.”

Though May was in many ways SFF’s face (and only employee) in those early years, our consistent messaging to the community underscored our purpose and core character: that we were an efficient organization for donors, that we were committed to the entire Bay Area region, and that our primary goal was to provide funding that would make a real impact, “improve conditions and facilitate change.”

SFF envisioned ourselves as risk-takers, a kind of “venture capitalist for nonprofits” able to fund “new ideas and minority interests that lack the broad constituency needed for government support or are too risky for other private funders.”

During our first five years, most grantmaking was focused on “social welfare” programs aiding schools, hospitals, churches and service organizations. While much of SFF’s assets remained unrestricted, by 1954, we began managing substantial and perpetual trusts earmarked specifically for use “in the field of race relations” and to “seek to reduce racial tensions.”

Did You Know?

By the mid-1950s, SFF began to establish a clear grantmaking philosophy with a distinct focus on fostering “equality of opportunity,” especially in terms of housing, employment and legal assistance, which remains consistent through our racial equity work today. Read about SFF’s Equity Agenda.

In 1954, the Supreme Court took an important stride toward justice with its 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The following year—with the horrific murder of Emmett Till and the Montgomery bus boycott—gave rise to a national civil rights movement strengthened by powerful organizations and leaders. May defined the foundation as one that should “try to equalize opportunity in every way.” He thus established an early model of an equitable racial policy, asserting “the board’s willingness to deal with gross social inequalities” and carve out an ideological niche for ourselves by specifically addressing race, according to scholar Jiannbin Lee Shiao.

While May and the early foundation made important shifts to meet the moment, we were still far from centering the Black community in our funding decisions. White supremacy culture and the way it informed early models of charity (rather than funder-grantee partnerships) was palpable. In fact, by May’s own account, the Urban League, together with a number of other Black-led and Black-serving organizations, wrote a letter to May accusing him of being racist. Said May in a 1976 oral history:

When you’re dealing with a community like the Black community, which has gotten so much more demanding since the ’54 Supreme Court decision, that it’s not going to pattern itself on the way the larger community or the establishment community behaves. It’s going to be very abrupt and militant and forceful and defensive—and offensive, too; and it’s just to be expected, it seems to me, the standards that we would expect of an organization run by and on behalf of the middle-class establishment are just not going to apply.

Learn how SFF invests in Black-led organizations today.

We attracted half a million dollars from donors by 1955, and by 1962, that figure had reached nearly $5 million, making possible $600,000 in grants, including significant support to the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association to focus on neighborhood relations. Across the country, calls for racial justice and equity were escalating, as activists—who were too often met with violent suppression—sought to overturn Jim Crow laws that affected almost every aspect of life in the South, including public transportation, education and voting.

The 1960s were a heady, turbulent time in the Bay Area, characterized by much more than Haight-Ashbury and the Summer of Love. Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panther Party in Oakland in 1966, helping to ignite a Black power movement around the country. At San Francisco State University and the University of California, Berkeley, the Third World Liberation Front organized some of the country’s longest-running student strikes in 1968 to protest a lack of racial diversity in curricula and among faculty and students. In 1969, Indigenous activists began a 19-month occupation of Alcatraz Island to protest the U.S. government‘s continued illegal seizure of their land.

Did You Know?

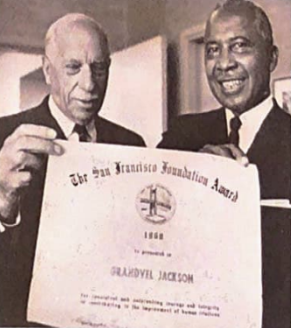

By 1968, our 20th year, SFF had distributed nearly $7 million, covering an increasingly diverse slate of issues that remain important to us today. Grantmaking included generous investments for “minority employment” (Bayshore Employment Service), a “seminar on race & poverty in higher education” (California Council for Educational Opportunity) and a “minority adoption project” (Children’s Home Society of California). The two largest grants SFF approved that year were a $45,000 grant for a “Black culture program” at the San Francisco College for Women and a three-year $100,000 grant to the NAACP to fund a new San Francisco office.

By 1968, we had hired our first program staff. Three years later, Rudy Glover was hired as assistant director, becoming the first Black staff member and first staff member of color. That same year, in 1971, investment banker Ira Hall became the first Black member of the Distribution Committee. In 1974, women comprised two members of the board (and for the first time, their first names were listed in the annual report). Learn about SFF’s diverse board today.

We were increasingly focused on newly organized neighborhood groups and hyperlocal issues—particularly those related to racial equity, as reflected in a 1972 summary of SFF’s field of interest:

A commitment to equal opportunity [and] a conscious attempt to mitigate the handicaps of disadvantaged groups—disadvantaged by language or race or cultural differences, by poverty, by physical, mental or emotional distress, by age or by birth out of wedlock. It is clear that a proposal under consideration by the Distribution Committee “has more going for it” if its purpose is the remediation of one or more of these inequities.

Still, John May contended that in our first quarter century, we had achieved far more in the way of mobilizing donor support than effecting change in the community: “I don’t take very much pride in the program development during my 26 years … I don’t think we on the staff really ever did as much planning for ways to determine what the community’s primary needs were.”

Establishing a Social Justice Point of View: The 1970s and 1980s

In 1974, after 26 years at the helm, May ceded leadership to Martin Paley, who had served on a social planning council and as a public health planner for hospitals and medical schools. Paley had no prior foundation experience and brought with him more of an activist orientation. The organization that May helped build now “had $38 million, a staff of two program people and two or three office people and a tremendous reputation,” remembers Paley. SFF had also become large enough to commission reports on the arts, health and public interest law, a more rigorous and academic approach that shaped our grantmaking practices.

In the 1970s, we deepened our commitment to a number of areas including the arts, believing, in Paley’s words, that “the community was more than a collection of problems; the community was an expression of creativity and the arts.” Additionally, between 1970 and 1981, SFF provided more funding than any foundation in the country to LGBTQ2SIA+ organizations. During this key civil rights era, we also played a significant role in seed-funding disability rights organizations, including the Center for Independent Living, to support the full inclusion of people with disabilities.

By 1980, SFF’s assets totaled $348 million, making us the largest community foundation in the country. That figure increased to $600 million by 1984, making SFF both “the largest community foundation in the country and the 15th largest foundation overall, including private and corporate foundations,” by our own reckoning. Much of this growth was due to the surprising and enormous windfall of the Buck Charitable Trust—which would soon put SFF in a uniquely uncomfortable position—alongside nearly 100 other charitable trusts.

Early 1980s programs expanded to include housing, childcare, teacher training, water policy, minority involvement in civic affairs, and emerging and minority arts (which is still one of SFF’s priority areas). Although the loss of the Buck Trust in 1986 led to major restructuring and rebuilding at SFF, social justice remained front and center throughout this transitional era.

“We worked diligently to create a community that was interdependent and that was open and accepting, and allowed for opportunity for all groups,” Paley said. “I think to have superordinate goals that can be shared across different, distinct communities builds a sense of respect, interdependence and comfort.”