Nearly 40 years ago, in 1986, SFF faced the biggest and most unique challenge in our history. The value of a gift—the Buck Trust—had skyrocketed overnight, and the donor intended for all grants from her trust to go to nonprofits in Marin County. We found ourselves in the uncomfortable position of granting tens of millions of dollars each year (far more than we granted to all other counties combined) to the wealthiest county in the Bay Area.

Under tremendous pressure from community organizations outside of Marin County, SFF lawfully petitioned to revise the terms of the trust in order to distribute grants throughout the Bay Area based on where needs were greatest. In 1986, we lost our petition, and the Buck Trust was transferred out of SFF to establish the Marin Community Foundation (MCF). Today, SFF and MCF are united in our efforts and partnerships to address racial equity and economic inclusion in Marin County and throughout the Bay Area.

As we celebrate our 75th anniversary this year, we look back with great empathy for everyone who was involved in and impacted by this case: the nonprofits and communities they served, the generous donors who wanted to invest in the places and causes they cared about most, and the SFF team that was faced with uniquely uncomfortable decisions.

We also reflect on this part of our history knowing that SFF would not face such a challenge today for a number of reasons. First, we work with donors to fully explore the implications of any gift restrictions, both in the present and in anticipation of the future. Second, rather than focusing on concern over “philanthropic saturation,” we partner with donors to find intersections between their philanthropic interests and our commitment to meeting the greatest needs in our Bay Area region. Third, whenever possible, SFF immediately sells any gifts of stock. Finally, we have a fund committee today that strictly adheres to donor intent and, as often as possible, finds intersections between donor intent and meeting the needs of our community.

The Buck Trust helped make us a stronger and more committed community and philanthropic partner, working with donors to fulfill their charitable vision while at the same time helping advance racial and economic equity in the Bay Area. Learn more about the donor experience at SFF.

The Buck Trust: A Deeper Dive

While no one can predict the future, early philanthropists correctly guessed they would need a mechanism to allow charitable dollars to evolve with the times. Frederick Harris Goff, founder of the Cleveland Foundation, the nation’s oldest community foundation, described the role of the community foundation as one that would not only give “a man the assurance that his property will be used for the purposes he intends … it will always be of the widest possible service to the community in which he lives.”

This notion was put to the test in the 1980s in the landmark case of the Buck Trust.

In 1975, former nurse Beryl Hamilton Buck died in Ross, California. A longtime resident of Marin County who had no children, Buck set up a trust with SFF based on her late husband Leonard Buck’s financial interests, which included a 7% stake in the Kern County-based Belridge Oil Co. This gift was estimated to be worth around $7.6 million at the time, all of which was to be granted to nonprofit causes in Marin County.

But after the 1970s energy crisis, oil prices skyrocketed, and in December 1979, Shell Oil Co. purchased Belridge for $3.65 billion. Overnight, this huge acquisition increased the value of the Buck Trust to about $260 million (equivalent to more than $1 billion today. The current value of Buck Family Fund assets is $800 million). And the valuation continued to escalate: by the early 1980s, the trust’s value had grown to $360 million. With the Buck Trust, SFF had become the 11th largest foundation in the United States.

All of this meant a windfall of roughly $30 million per year, all to be spent in Marin County.

Did you know?

Once the value of the Buck Trust became clear, SFF began fending off what Paley termed “carpetbaggers … people from all over the country who suddenly want to bring their talents to the people of Marin.” The New York State Symphony director tried to move his orchestra to Marin, for instance, despite being unaware that the county already had a symphony and being unclear on where Marin was located.

In 1980, as now, Marin County had the lowest unemployment rate in the Bay Area, the lowest number of Medicare enrollees, and the lowest number of people living below the poverty line. Marin was home to 7% of the Bay Area‘s population, and more than 92% of its residents were white. SFF’s Marin County grants represented three times the amount we were spending in all other Bay Area counties combined, and it was also roughly the same amount that Marin County was spending annually for all of its mental health, social service and welfare programs.

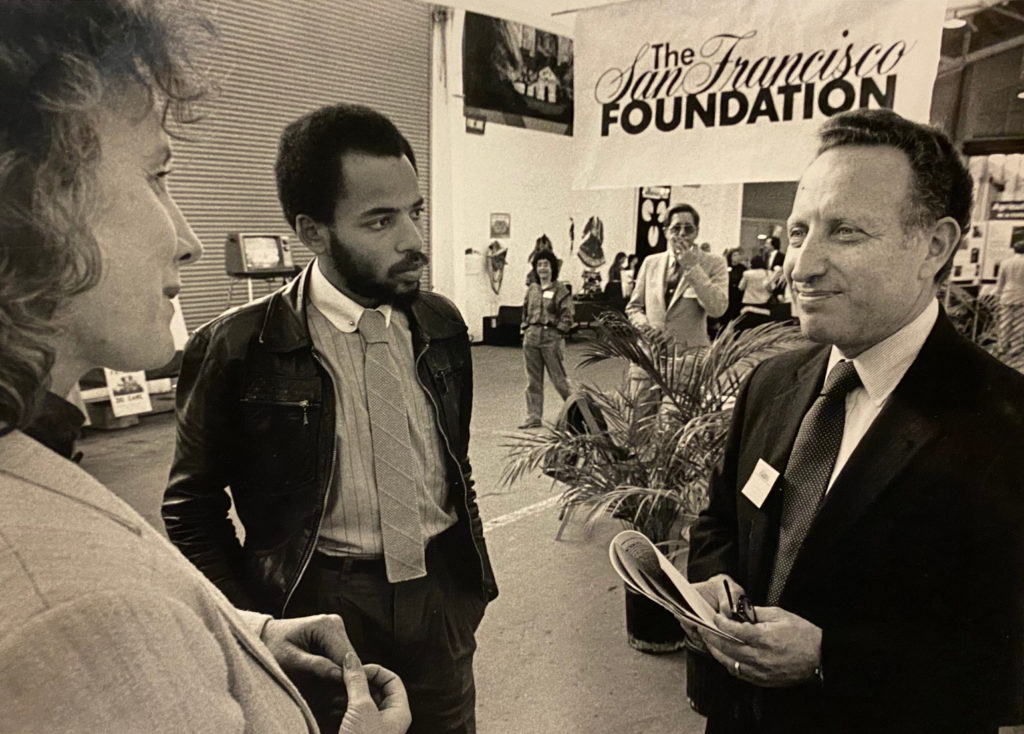

Despite the longstanding legal doctrine of cy pres, there was no precedent for such a large and sudden windfall in the history of American philanthropy. SFF director Martin Paley and the foundation staff realized their response to this unique situation would stand as a landmark.

In July and August 1979, SFF organized a series of five meetings with 85 community leaders throughout Marin County to hear directly what the community needed in terms of programs and services. We held another round of meetings—open to the public—throughout Marin in March 1981. “It was a basic, fundamental belief in the importance of the people to be involved in their own future and not to sit back and feel that because [SFF] had the money, [we] also had the wisdom,” Paley said. “The wisdom was in the community. And we sought to find that wisdom and bring it forth and then feed it back to the community in programs and grants.”

Paley also traveled the country speaking with experts to gain a better understanding of the ethics of the unique situation. The Distribution Committee spent three years contemplating the complex issues at stake while funding bold projects in the county, including many nonprofit programs and government projects.

“As you can imagine, with a community such as Marin, it’s not easy to spend $30 million in a year,” Paley said. A member of SFF’s Distribution Committee during the Buck Trust era put it more bluntly: “We’ll be able to spend money in Marin until every last rut in the county’s roads is filled.”

“We worked like the dickens, we tried, and then we began to wonder, is this the way that Mrs. Buck would have done it if she had been alive?” Paley said. “She was a prudent woman. She might have thought that was more money than could be wisely used in Marin and would have perhaps put other conditions on our bequests. And that’s where we began to run into some interesting times with the court.”

Petitioning To Broaden the Trust

Did you know?

During our five years administering the Buck Trust funds, SFF distributed more than $134 million to Marin County, with about $37 million going to community health and human services grants, focusing on “treatment, rehabilitation, promotion and maintenance of physical, social and mental health, with priority to programs addressing the needs of the elderly, ethnic minorities, children and families.” We allocated Buck funds totaling $25 million to programs focused on affordable housing and urban affairs, and nearly another $25 million to education. There were questionable grants during this period, too, including $20,000 to a homeowners‘ association to hire a professional swimming coach. The association’s charitable activities consisted of maintaining a members-only clubhouse and pool.

After years of deliberation, legal consultation, and mounting pressure from community organizations throughout the Bay Area, SFF sought a compromise. Exercising our cy pres discretionary powers, SFF petitioned the Superior Court of Marin County to continue Marin-exclusive grantmaking for another three years, spending roughly $90 million, and then begin making part of the Buck funds available to other Bay Area programs while continuing to prioritize Marin projects.

Among those who publicly advocated for the Buck Trust grants to continue to be spent in Marin County were the county’s board of supervisors and the Marin County Bar Association. But SFF also had plenty of supporters who agreed with our petition to modify the Marin-only restriction. Those included the public interest law firm Public Advocates, which represented 28 non-Marin nonprofits, and California Attorney General George Deukmeijian, whose office in 1980 expressed concern that the grants might result in “charitable saturation” in Marin County. National and local media alike, to a large extent, also raised concerns about the appropriateness of the Marin-only restriction.

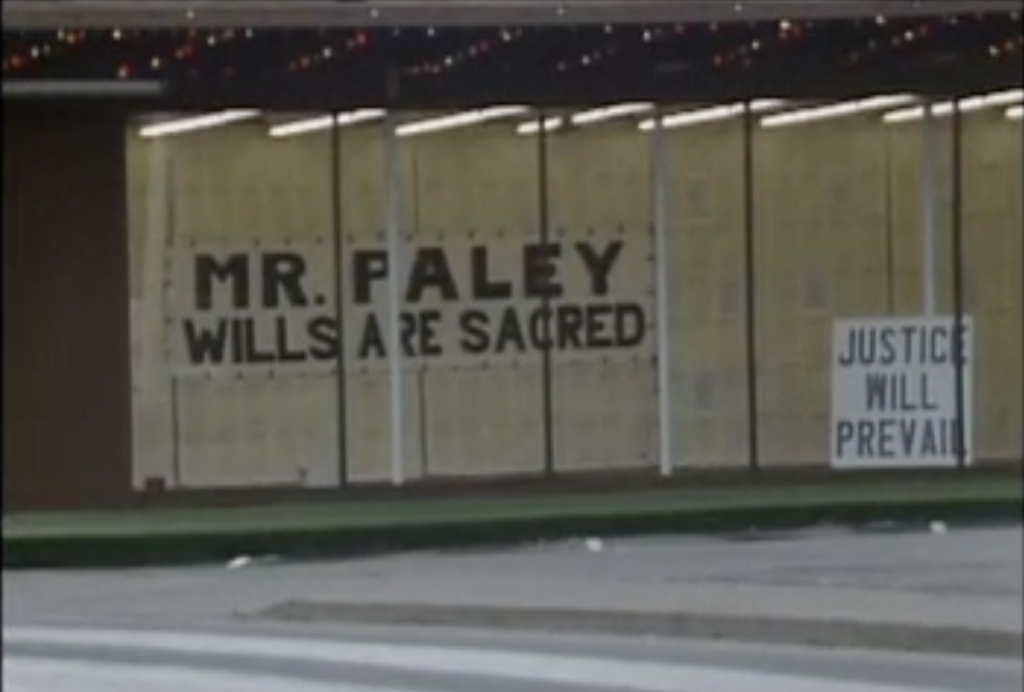

“As you might expect, a lot of people in Marin got very upset with that notion that we would go to court and seek a modification,” Paley recalled. “It touched off a firestorm that was quite significant. It was painful. It was a very, very challenging time for the board, for the staff, for the community and for the Bay Area.”

It was painful for Paley as well, as the attacks from Marin soon grew personal. “[SFF’s] petition was characterized as a threat to the sanctity of wills and the health of philanthropy, and as an offense against capitalism, the American way of life, and God,” wrote Yale Law School deputy dean John G. Simon. “Foundation personnel were said to be corrupt and dishonest and, in the language of a Marin County supervisor, ‘grave-robbing bastards.’”

“There was so much trauma for our program officers at the time. It was a lot of personal attacks on them,” recalled Retha Robinson, who joined SFF in 1980. “We kind of formed a support system for ourselves and just really tried to take care of each other.”

Nevertheless, we stood our ground, and in 1984, Paley referenced regional interdependence in his final appeal to the Marin County Chamber of Commerce and to donors present and future:

The Distribution Committee sincerely believes that, on reflection, people who are considering gifts to the San Francisco Foundation will view the current action in trying to protect the enduring usefulness of the Buck funds as an act of responsibility and courage in keeping with the great traditions of philanthropy, and that they will be all the more willing to entrust their gifts to the foundation. … We would hope that on reflection the people of Marin will recognize that they are citizens of a larger community—the Bay Area—where many of you go to work, to play, to enjoy cultural and sporting events or, in times of crisis, to seek medical and other care. Continuing to expend a vastly disproportionate share of charitable dollars to benefit less than 7% of the Bay Area’s population would place a strain on that larger community.

After five months of debate, the court made clear their opinion that the funds should continue to be used exclusively in Marin, extending to “major projects” with national-international appeal, thus exercising its own version of cy pres doctrine. A new Distribution Committee took over at SFF and requested a settlement. They resigned the Buck Trust to a group in Marin that went on to establish the Marin Community Foundation, and Paley was ousted. More than half of SFF’s staff was laid off.

However bittersweet, “there are a lot of lessons in this experience, and it should be a part of history,” Paley reflected in 2021. “And I think just as we are denying the history of our nation—in many respects, we’re ignoring it—I think embracing the full experience and history of the foundation and philanthropy is absolutely essential to going forward.”

Staunch supporters of SFF’s position included John G. Simon, former deputy dean of the Yale Law School, who wrote that SFF:

… has established an important precedent in the annals of American philanthropy. It has faced up to the highest duty of trusteeship: to address difficult and novel dilemmas involving the fiduciary mission, to do so in a way that seeks to respect both the donor and the public interest, and then, having resolved the dilemma, to act upon that resolution, regardless of slings and arrows. … The health of the American nonprofit world, and of the private sector in general, is a bit more robust because the foundation grasped the nettle in the Buck Trust case. A congeries of pressures, some of them disreputable and all of them powerful, forced the foundation to withdraw short of the final goal, but its effort to that point, in my view, merits the philanthropic equivalent of the Medal of Honor—plus, of course, the Purple Heart.

SFF’s current CEO Fred Blackwell frames the Buck Trust challenge as one that offered an opportunity for SFF to flex our leadership and values: “The loss of the Buck Trust was really about the fact that the foundation was emerging as a philanthropic institution with a point of view around meeting the needs of the most vulnerable in the Bay Area.”

The Buck Trust was an extraordinarily unique case, the likes of which the philanthropic sector hasn’t seen again for nearly 40 years. Today we take pride in SFF as a trusted philanthropic partner for hundreds of donors and thousands of community organizations who, together, share our vision for an equitable and inclusive Bay Area.