[The establishment of the San Francisco Foundation provides the community with] a contemporary agency sensitive to current social needs, and one which will help build a future which will magnify the opportunities of generations yet to be born.

Edward L. Ryerson, Chairman, Chicago Community Trust, January 16, 1948

A New Model for Social Change

World War II transformed the Bay Area into the center of the nation’s military and industrial complex. Nearly two million soldiers, sailors and civilians passed through San Francisco en route to Asia. Cities and towns saw their populations surge, some by fivefold. And it wasn’t just sheer numbers that were changing; it was also the racial makeup of the Bay Area. The U.S. government ordered the mass removal and imprisonment of the West Coast’s entire Japanese American population, one of the region’s largest communities of color. The Bay Area’s Black population grew from 20,000 in 1940 to 150,000 in 1950. Although the economy boomed with war contracts, not everyone thrived.

It was amid this postwar climate that a group of public servants, philanthropists and business leaders unveiled a daring idea to create a Bay Area where everyone could thrive: a foundation that would keep community at its center and one that donors could entrust with their gifts, understanding that this new organization was best positioned to address the region’s most pressing issues then and in the future.

For Generations Yet To Be Born

It was 1948, and a throng of guests had gathered inside the Sir Francis Drake Hotel in downtown San Francisco. With its gold-leaf ceilings and hand-painted murals, it was one of the city’s most expensive and luxurious buildings—and, until 2022, a building named after one of England’s earliest enslavers of African people.

Guest speaker Edward L. Ryerson marked the inauguration of the San Francisco Foundation with a message of patience and a long-term view of social change. “Community trusts are more like oaks than mushrooms in their growth patterns, and you should not be disappointed or discouraged if the first few years are a little slow,” said Ryerson, chairman of one of the oldest community foundations in the country: the Chicago Community Trust, which was established in 1915. “It takes time to throw out roots and become firmly established in the soil of public confidence, which is what really makes these institutions grow.”

Flanked by two of SFF’s three co-founders, Marjorie de Young Elkus of the Columbia Foundation and Daniel E. Koshland Sr. of Levi Strauss & Co., Ryerson touted the San Francisco Foundation as “one which will help build a future which will magnify the opportunities of generations yet to be born.”

With only $20 to its name, SFF was barely a sapling on our inauguration date of January 16, 1948. But SFF’s seeds had been germinating for many decades. Bay Area philanthropists had attempted to organize an earlier incarnation of the San Francisco Foundation in 1926 but abandoned the plans three years later as the nation entered the Great Depression.

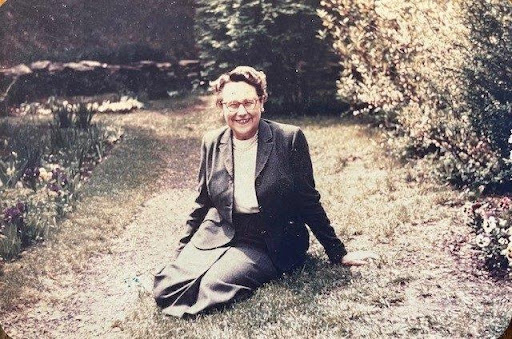

Co-Founder Marjorie Elkus

Born into a prominent family in Pennsylvania, SFF co-founder Marjorie Elkus was educated by Catholic nuns in Quebec before she earned her college degree in social welfare from the University of Pennsylvania. She went on to become a nationally recognized social welfare expert who served as the director of the California Emergency Relief Administration and the head of the Children’s Council of San Francisco’s Community Chest. She was also related by marriage to Charles de Young, the founder of the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1940, she shifted her career to philanthropy when she was tapped to serve as the first executive director of the Columbia Foundation, one of the first family foundations in the region.

Under her 10-year leadership, the Columbia Foundation focused on a number of social welfare programs, including significant support for Japanese American resettlement after the U.S. government’s unjust incarceration during World War II. But Elkus was frustrated by the Columbia Foundation’s family foundation model: “I began to feel that this business of giving money away [at a private family foundation] was too darn ephemeral for me,” Elkus recalled. “At any minute someone might change his mind or something could happen to one of the board or [the funding would dry up].” Her solution was to establish a different kind of entity: a community trust.

In the 1940s, when people wanted to donate money as a gift or a bequest, they would typically ask a bank to hold it in trust. But banks had no mechanism to give away this money; they had no trained staff with knowledge of social issues or experience in philanthropy. Elkus was determined to set up a new kind of foundation to fill this gap. Still a novel concept at the time, it would be guided by a Distribution Committee (now known as the Board of Trustees). “I realized that there was a great deal of money in this town that was not being used. So I decided we should establish another foundation,” she recalled in an oral history recorded by the University of California, Berkeley, in 1974–75. “This would be an entirely different one than [Columbia]. This would be more of a civic group, and we called that the San Francisco Foundation.”

Co-Founder Leslie Ganyard

Like Elkus, SFF co-founder Leslie Ganyard was a longtime public servant and foundation executive—positions that were rare for women to occupy at the time. A 1964 San Francisco Examiner article lauded her lifetime of service, albeit with a sexist description: “This buoyant little woman has been more closely associated with the social welfare movement in California, for more years, than almost anyone you can name.”

Ganyard hailed from a prominent and civically active family in Ventura, California. They were close friends with the George family, which had established a residential treatment center for teenagers in Freeville, New York (the nonprofit continues operating today as the William George Agency).

With a worldview shaped by these influences, Ganyard attended UC Berkeley, where she served as the women’s editor at the Daily Californian. She graduated in 1915, five years before women gained the right to vote, and went on to lead the university’s efforts in the 1920s to find employment for alumni who had served in World War I. By the 1930s, she was serving as the secretary of the San Francisco League of Women Voters, and in 1935, in the throes of the Great Depression, the state of California tasked her with heading the combined California State Employment Agencies and U.S. Employment Service in Los Angeles County.

After 20 years in the public sector, Ganyard pivoted to philanthropy in 1936 when she became the first head of the Rosenberg Foundation—and the first staff member at any foundation west of the Mississippi River. She was ready to hit the ground running. “How do you think we should set up this office?” she recalled being asked when she joined the Rosenberg Foundation. “With a desk and a telephone,” she replied. She led the Rosenberg Foundation for 22 years, supporting issues and communities including Japanese American resettlement following incarceration during World War II and California’s migrant farm workers. Ruth Chance, her successor, later described the Rosenberg Foundation’s first leader:

Leslie was gregarious. She really enjoyed visiting, and she learned a lot about the capabilities of applicants … through her unhurried and disarming discussions with many people. She would come into the office in the morning, answer all the day’s mail promptly, and then be out the door on her way to talk with applicants or visit projects, or just find out what was happening. She had traveled the state widely, trying to explain what a foundation was. … People had to be encouraged to apply.

Co-Founder and First Chair Daniel E. Koshland Sr.

It was two women, Mrs. Marjorie Elkus of the Columbia Foundation, and Mrs. Leslie Ganyard of the Rosenberg Foundation, who called me one day with a far-reaching idea: “We want you to help start a community trust,” they said. The phrase had a fine ring even then.

Daniel E. Koshland Sr. upon his retirement after serving on SFF’s Board of Trustees between 1948 and 1974

Did you know?

Corinne Koshland, the mother of SFF co-founder Daniel E. Koshland Sr., was one of the people connected to the initial 1926 effort to organize the San Francisco Foundation. In addition to his mother’s model of service, Daniel E. Koshland Sr. was also influenced by Herbert Lehman, former New York governor and senator, who mentored Koshland during his younger days in New York and inspired him to coordinate relief programs for boys in Lower East Side tenements, as well as programs to teach them literature and music.

To help get the idea of a San Francisco Bay Area community foundation off the ground, Elkus and Ganyard turned to Daniel E. Koshland Sr., the respected and well-connected head of Levi Strauss & Co.

Born and raised in San Francisco, Koshland’s grandfather and father were successful wool merchants. After studying economics at UC Berkeley, he moved to New York City, where he worked in finance. It was there where he met Herbert Lehman, then a partner at his family’s investment banking firm, Lehman Brothers. But Lehman was more interested in public service than finance: after leaving banking altogether, he would eventually become governor of New York and, later, a U.S. Senator. It was Lehman who first introduced Koshland to social work—specifically a volunteer role coordinating programs for Jewish boys on New York City’s Lower East Side. “I headed boys’ groups. Met maybe once a week, maybe oftener and guided them in English classes and literature, and music,” Koshland recalled in his 1971 oral history. “I found it very, very interesting. I think Herbert Lehman is responsible for that, too.”

After returning to San Francisco in 1917, Koshland joined Levi Strauss & Co. in 1922 as vice president and treasurer at the invitation of his brother-in-law Walter A. Haas Sr. Koshland would later serve as the company’s CEO between 1955 and 1958 and remained on the company’s board until his death in 1979. During his time at Levi Strauss, the company made a concerted effort to hire Jewish refugees who had fled Nazi Germany. Levi Strauss also became one of the first apparel businesses to give bonuses to its factory workers, refused to lay off workers during the Great Depression, and integrated the workforce at its factories well before the Supreme Court began to outlaw segregation in 1954.

Throughout his corporate career, Koshland remained extremely active in community service. In addition to co-founding SFF and serving on our Board of Trustees (then known as the Distribution Committee) for 26 years, he also served on a plethora of nonprofit committees and boards, including the United Negro College Fund, the Human Rights Commission, the San Francisco Juvenile Probation Committee, Planned Parenthood, the San Francisco Development Commission on Low-Cost Housing and the Council on Civic Unity. Between 1947 and 1951, he also served on California’s Industrial Welfare Commission where he helped determine minimum wage and working conditions for people in the Bay Area, circumstances he hoped would improve their lives.

When asked what inspired and sustained Koshland’s longstanding commitment to community, his grandson David Friedman answered:

I would start, in a word: people. I think it was this recognition of him being lucky and being privileged, but that the world was not fair … Even in those days, he could have had a choice of starting his own family foundation, but I think he saw the value in a community foundation. And I think … that’s how he thought the philanthropy could be centered around people and communities where it was needed the most.

Planting the Seed

With some modest seed funding from Elkus’ Columbia Foundation, the three founders brought together an exploratory committee to study the nation’s community foundations and develop the framework for a Bay Area equivalent. The group, with Koshland as its chair, included as its vice-chair an attorney named Gardner Bullis, who traveled the country interviewing other foundation leaders to discern their best practices and lessons learned. The 25-member committee included prominent lawyers, bankers and social sector leaders but, more notably, did not include community members directly impacted by inequitable systems. Read how SFF centers nonprofits in our grantmaking today.

Following these models, the committee drew up our charter, and SFF was incorporated. Koshland served as founding chair of SFF’s Distribution Committee, a critical body that made decisions about which causes and organizations to support (and would later become the Board of Trustees). In April 1948, the committee hired John R. May, who had previously worked at the Office of Price Administration, a federal department set up to control prices and rents after the U.S. entered World War II. For several years, May remained the only foundation employee.

Putting Down Roots

SFF, and in particular our Distribution Committee, has played an outsized role in the history of Bay Area social change and the philanthropic sector in general. Koshland noted “racial problems that [we] are trying to meet”—such as upstart tutoring programs for Mexican Americans in underserved areas. We were searching, in Koshland’s words, “for new, imaginative programs that have a promise of developing into something constructive and important in the community.” This philosophy continues to guide SFF’s approach to grantmaking today.

By 1951, Edward Ryerson’s appeal for patience had officially borne fruit. SFF had amassed some $88,000 in trust assets and granted more than $20,000 to local charities, and was well on the way to gaining the strength of an oak.

“The period of exploration and doubt is past,” Koshland wrote in our first annual report in 1951. “The future, it is evident, will justify the growing pains, the patience, and the faith which characterized the first three years.”

Because of this patience and resilience over the past 75 years, SFF now stands as one of the region’s core conduits for change, with roots extending throughout the Bay Area.