To me, leadership is really about how you wield power. It is not about power itself. The intentionality with which you think about how you influence people to make systemic change is something that I believe all leadership programs should be teaching and encouraging.

Sandra R. Hernández, M.D., SFF CEO (1997–2013)

Recovering From the Buck Trust Loss (1986–1996)

Lawyer and former Lafayette Mayor Robert M. Fisher joined SFF in June 1987, about a year after SFF’s loss of the Buck Trust. Fisher intended to rebuild our pipeline of donors and assets under management in order to restore the size of our grantmaking budget.

During this time, we chose to stay under the radar, out of the front-page news, and away from bold or controversial initiatives. California’s 1994 anti-immigrant legislation, Proposition 187, was one example of our reluctance to take a leadership position on a core social justice issue. Despite funding immigrant and citizenship services, SFF maintained a low profile on the topic, refraining from putting our logo on any campaign literature.

Did You Know?

In 1990, SFF established our first diversity policy, requiring potential grantees to provide demographic data on their boards and staff and encouraging “them to achieve an institutional diversity that reflects the communities they serve.”

With regard to financial recovery, Fisher’s tenure, which ended in 1996, was successful. A 1996 foundation newsletter touted the era as “marked by tremendous growth in assets (from $150 million to more than $400 million), contributions (from $5 million a year to nearly $30 million), and grantmaking (from $7 million a year to more than $30 million), by a 500% increase in the number of funds advised by living donors, by an increasing diversity of board, staff and grantees.”

SFF’s new direction—focused more on donor contributions and asset growth rather than community impact and partnership—didn’t land well with everyone, including our own team. Waves of staff resigned, as did board member Herman Gallegos in 1992. After Fisher’s departure in 1996, longtime program officer John Kreidler became SFF’s interim director until Dr. Sandra Hernández was hired in 1997.

It was now time to reconnect our roots to local communities.

The Sandra R. Hernández, M.D., Era (1997–2013)

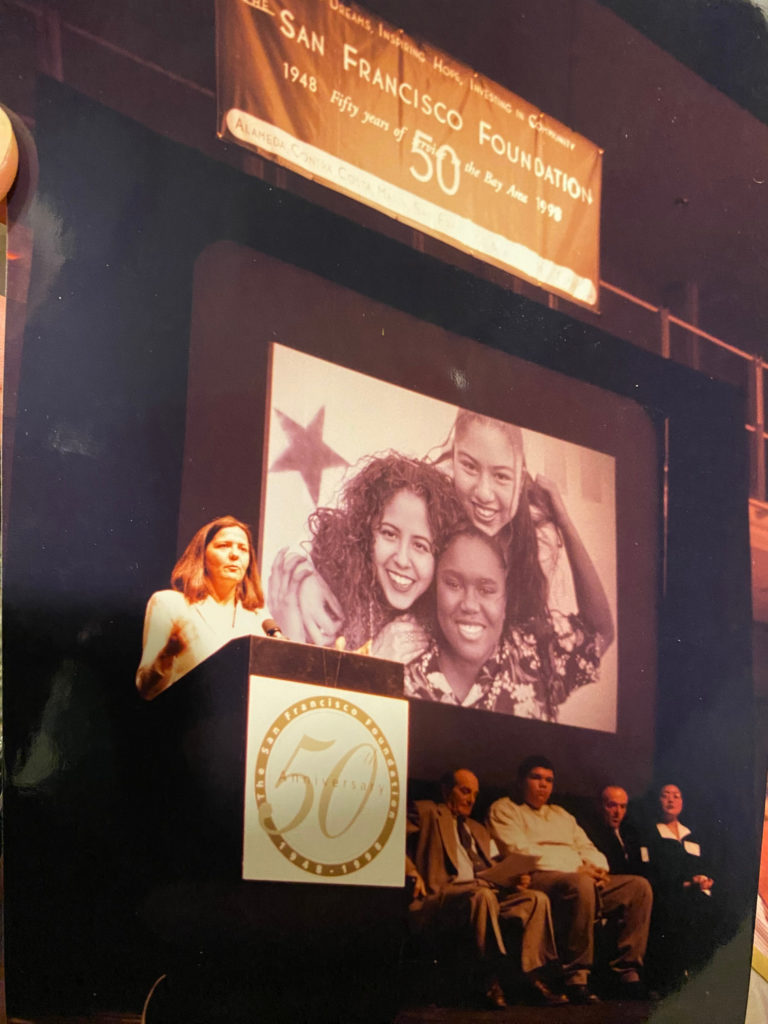

Following this decade-long rebuilding period, SFF hired Sandra R. Hernández, M.D., a practicing physician and director of public health for the City and County of San Francisco, as CEO. Hernández swiftly restructured, building up our management team, and worked with Board Chair and renowned investor Warren Hellman to manage our endowment in-house. In the run-up to SFF’s 50th anniversary in 1998, Hernández jettisoned our traditional, staid black-tie gala in favor of a more inclusive slate of events: a block party, a youth communications expo and a roundtable forum to help shine light on the problems, ideas and hopes of youth in the Bay Area.

“In some ways, it was a coming-out party for the foundation coming off of a post-Buck Trust [era],” Hernández recalled. “I think people felt like we put the ‘community’ back into the community foundation.”

As the first woman, person of color, and LGBTQ2SIA+ CEO of SFF, Hernández’s era marked a clear shift in terms of not only representation but also the high-profile issues we were again prepared to take on. It was about “going beyond the check and really thinking about the organizing and influence that the San Francisco Foundation became known for,” said Hernández’s successor and current SFF CEO Fred Blackwell. “Sandra’s leadership was, I think, a lot about policy systems change, taking bold action on thorny issues and really exercising that leadership muscle at the San Francisco Foundation.”

After leading an early effort to overhaul the region’s vast network of neighborhood parks and bolstering SFF’s support for our Daniel E. Koshland Civic Unity Program and Multicultural Fellowship Program, Hernández’s administration turned its attention to healthcare.

With her background in the public sector and a specific focus on public health, Hernández led the way in early pilots to health care reform. From 2006 to 2008, Mayor Gavin Newsom and Supervisor Tom Ammiano directly tasked Hernández with the development of a plan for universal healthcare—the first municipal program of its kind in the United States—creating the Healthy San Francisco initiative.

Hernández also understood that public health is deeply impacted by other economic factors, such as housing, so in the same year, we also partnered with the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Enterprise Community Development to create HOPE SF, an ambitious program to transform affordable housing in San Francisco’s Hunters View, Alice Griffith, Potrero Terrace and Annex, and Sunnydale-Velasco neighborhoods.

The initiative centered on our partnerships with the public sector, nonprofit partners and resident leaders to combat systemic racism and transform the dilapidated conditions of public housing in the Bay Area.

Did You Know?

Led by the Evelyn and Walter Haas Jr. Fund, SFF was among the first community foundations to publicly fight Prop 8—a ballot measure intended to ban gay marriage in the state—paving the way for other California community foundations to join the fight for marriage equality. The communications campaign continued beyond the ballot box, and Proposition 8 was overturned in 2010, with the U.S. Supreme Court denying an appeal and same-sex marriage becoming legal in California in 2013.

Among these and a host of other accomplishments, Hernández’s administration also put a major stake in the ground by taking a leadership role in the fight for marriage equality, opposing a 2008 statewide ballot measure known as Proposition 8 intended to eliminate gay couples’ right to marry in California. In combating the discriminatory measure, we became one of the first philanthropic organizations nationwide to publicly take sides in the high-profile referendum.

“As a community foundation, you’re a public charity, and thus you can take positions on ballot measures,” Hernández said. “I went to [the board] with a recommendation that we take a position on marriage equality as a value proposition. … It was the first time the foundation had ever done that—taken a position on a ballot initiative. We studied it, we leaned in, in every way we could—publications, polls, those kinds of things—and it was the right thing to do.” Read about SFF’s policy work today.

Restructuring Foundation Governance

One of Hernández’s most significant accomplishments was overhauling the structure of our Board of Trustees. When Daniel E. Koshland Sr. first established SFF’s Distribution Committee (later known as the Board of Trustees) in 1948, he modeled it after the Cleveland Foundation, the first community foundation in the country. That meant each trustee was selected by the presidents of seven of the Bay Area’s largest and most established institutions: the United Community Fund of San Francisco, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, the University of California, the trustee banks, Stanford University, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, and the League of Women Voters of California. Together, these appointing authorities represented some of the most powerful civic and business organizations in the region. Starkly absent from the board, however, was representation from the communities that we served.

At times, this board structure hampered SFF’s ability to take stances on key issues of equity. In 1996 and 2003, for example, SFF didn’t take a public position on Proposition 209 or Proposition 54, respectively. Both were anti-affirmative action measures led by UC Regent and conservative activist Ward Connerly. With one of our trustees appointed by the UC Regents, SFF even hosted Connerly at our office at least once. On another occasion, Connerly was invited to speak at a public debate SFF hosted on affirmative action. When Connerly did not show up, Ron Rowell, SFF’s social justice program officer, awkwardly stood in and argued for Proposition 54’s conservative merits.

In 2002, Hernández and Board Chair Warren Hellman set out to modernize SFF’s governance structure by shifting its legal form from a trust to a nonprofit public benefit corporation, thereby also creating a fully self-appointing board. With trustees such as Tatwina Lee of the Chinese Culture Center and Radio Bilingue founder Hugo Morales joining the board in 2002 and 2003, the change—and the board‘s closer connections to the community—was immediate. “We had people that were very active in the civil rights movement that were on the board. We had people who came from very different walks of life, which you want in a community foundation,” Hernández said. “And so that was a really important part of taking the helm of an organization at 50 years and saying, ’What does it need to be going forward?’”

Setting the Stage for SFF Today

Says Lew Butler, a mentee of Daniel E. Koshland Sr. and co-founder of SFF’s Koshland Program: “Sandra was the greatest thing at the time that could happen to the foundation. She straightened everything else out. From my standpoint, she was the person that saved the foundation, and it’s been on an upswing ever since.”

Under Hernández’s leadership, SFF’s policy advocacy and bold public stances on key social justice issues were a clear departure from our previous era. Our deepened commitment to social justice during this era was also a vital precursor to the next period in our history, shaped by Fred Blackwell’s leadership and redoubled efforts around racial equity and economic inclusion—our North Star.